Introduction

I’ve worked alongside many teams and engineers and have been part of the Encode tribe here at Alamy for two years. We have been tracking quarterly team health check scores, and estimation seems to be the topic that fluctuates the most, ranging from 50% to 88%.

N.B. Team/ tribe makeup has significantly changed over this period which can explain some variances.

As we approach a new year, this article is designed to provide a shared understanding of agile estimation and facilitate a consistent interpretation of estimation effectiveness so that we can trust the survey results reflect team practices and help identify tangible areas for improvement.

Lets start with the all-important why:

Why do we estimate?

I believe at its core, estimation is all about the conversations it provokes. Estimation helps foster communication and allows us to set short-term expectations, creating transparency and a shared understanding across teams and our stakeholders. Once this shared understanding is established, with an agile lens we have something that we can continuously inspect – and the power of this is that we have the means to adapt and update expectations and plans accordingly.

It’s about setting realistic expectations for the team, stakeholders and other business units or suppliers that rely on project timelines and have considerations such as resource planning.

Good estimation allows us to foresee potential risks, allocate resources appropriately, and manage timelines without overwhelming the team. Without it, we can fall into familiar traps: delivering late, overshooting budgets, or sacrificing key features to meet deadlines. Even when deadlines are met, it often comes at the cost of overworked team members, resulting in burnout, frustration, and possibly higher attrition. Not to mention there’s a higher risk of introducing bugs and technical debt if there’s a sense of urgency and a temptation to cut corners.

Inaccurate estimates lead to flawed plans, which frustrate the teams trying to execute them and the stakeholders counting on them. I have witnessed big cultural impacts as a result of poor estimates. Team friction and micromanagement often arise when estimates are weaponised or misunderstood as guarantees. When there’s no credibility in what the team says – it’s understandable that there is a risk that they’ll no longer be listened to.

Estimation, when done right, isn’t just a guess – it should foster trust through transparency and communication and is a crucial tool for navigating complexity, managing expectations, exposing risks and delivering successful projects. Teams that embrace collaborative estimation and refine their practices through inspection and adaption become more predictable, which leads to a more sustainable pace and autonomous way of working for teams with less stakeholder friction and missed deadlines.

The Challenges of Estimation

Unknown unknowns

Traditionally, we’ve evolved as humans to trade and establish a contract and price for work undertaken or goods to be purchased. No one would expect a tradesperson not to give them a firm timeframe and price on the work they intend to have them do. We operate in the same way today, our leadership teams require accurate information to aid their decision-making and help track the viability of suggestions and ROI.

Something worth diving into here is the significant shift in domain space over the last century. A key consideration for us is that we often operate in a complex domain. It’s known that being accurate and predictable is near impossible in this domain – we often have ‘unknown unknowns’ to contend with and as we begin to work through requirements, options, scope and considerations surface which could greatly impact forecasts.

Below is a Cynefin diagram that exists to help us realise that all situations are not created equal and to help us understand that different situations require different responses to successfully navigate them.

Different problems warrant different solutions – see more here Cynefin

Imagine planning a new software platform versus updating a familiar system. Building a new platform involves many unknowns, such as integrating with third-party systems or accommodating evolving user needs. This is similar to building a skyscraper, where unexpected challenges (e.g., soil conditions or supply chain delays) make upfront planning less reliable. In contrast, updating a familiar system is like renovating a single floor, where the scope and risks are more predictable.

Questions you could consider in your team sessions might be:

- are we dealing with complexity and if so we need to explore options and present problems to solve over solutions

- are we working in a simple (or obvious) domain, fixing bugs as a potential example – we know the code – we’ve worked on something similar recently?

- Complicated sits in the middle, and warrants its own exploration and question set, for example, can we identify a clear sequence of steps or dependencies that must be followed? Do we already have access to subject matter experts or specialists who can guide us through well-established processes?

Answers to these questions help inform which approach would be most relevant. I mention this because we’ve seen in our Lumos squad work that falls within the devops type domain tripping us up – our approach has started to shift, drafting in hands on assistance from SA’s/ Platform engineers – which is great and a really good example of us inspecting and adapting, ultimately improving our workflow.

We encourage complex work to be broken down into smaller milestones and estimates to be continuously refined through the inspection points enabled by working in an agile way (sprint reviews, retrospectives, cycles/sprints etc.) rather than based on fixed upfront assumptions and decisions.

Features and product backlog items we are working through now or next tend to be well understood and broken down into deliverables that can be completed in a cycle, in other words, understood and estimated accurately, whereas those items in the later sphere (or lower in priority) may have a rough t-shirt size assigned to them as a guide with the caveat that it’s subject to change.

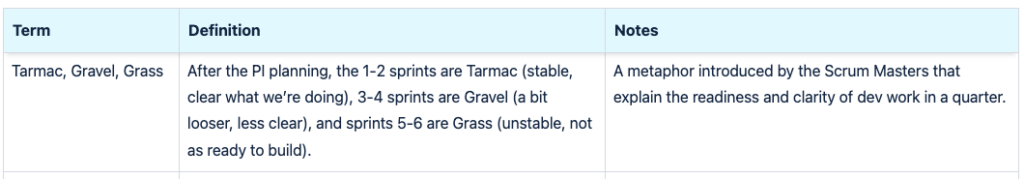

In the past, we have used the grass, gravel and tarmac metaphor to explain this. Glossary

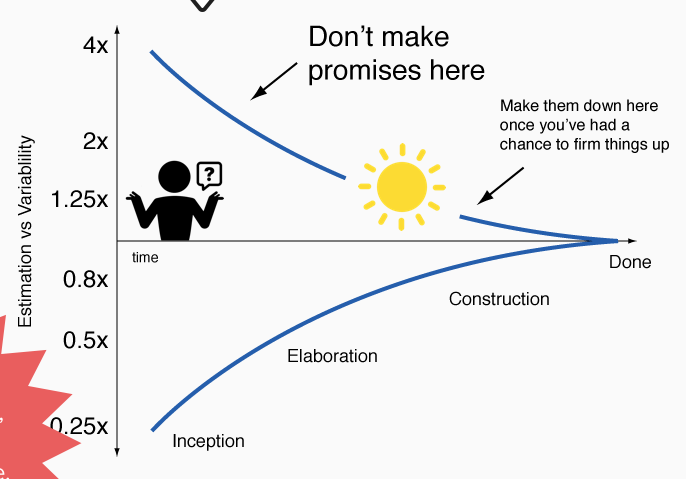

The cone of uncertainty is also worth a mention. As requirements become clearer, or the domain shifts away from complex, estimations become more reliable.

The Cone of Uncertainty, described by Steve McConnel, shows what any experienced software professional knows. Which is at the beginning of any project we don’t know exactly how long a project is going to take.

Acknowledging the cone of uncertainty allows teams to proactively manage expectations and surface risk factors to their leadership support team. If there is a clear presence of uncertainty (say for example early estimate or unknown greenfield requirements or unfamiliar tech stack, or tech stack known to only one or two team members) these estimates should be higher or treated as ranges, narrowing as work progresses and more information becomes available. Ideally, we’d be better off being transparent upfront than find ourselves in a tight spot having accepted lower estimations and thus set some level of expectation we then have to reforecast. This isn’t about adding bloat to cover our backs – it is being mature and raising a potential risk when it is appropriate to do so. Once we have the transparency – we have options. The work could be approached differently for instance.

Human Biases and Differing Perspectives

Humans are naturally optimistic and often biased toward seeing goals as more achievable than they may truly be. This optimism can lead teams to underestimate the complexity, time, or effort required for tasks, especially when dealing with unknowns.

Engineers and teams may also have differing perceptions of what constitutes “effort” or “size” due to varied experiences, skill levels, or familiarity with the domain. These differing viewpoints can create misalignment when interpreting relative units like points or sizing. We incorporate practices such as Planning Poker to surface differing perceptions of effort and size among team members. For example, one team member may view a task as a “3” due to familiarity, while another might see it as an “8” due to perceived risks or unknowns.

Recognising and addressing these biases through collaborative conversations and calibration exercises is essential to improve alignment and foster shared understanding. There’s richness in the conversations that surface here is important – use the cues to explore further not just as a negotiation to round up or down.

We have a general consensus from a calibration exercise we carried out in 2024 here as a reference point, Team Norms | Estimation which we will continue to revisit when it feels necessary to.

The Value of Estimation

As a summary, this isn’t an exhaustive list but the core areas that benefit from good estimation practices include:

- Facilitating rich conversations and collaboration.

- Building credibility and trust within teams and with stakeholders.

- Maintaining a sustainable pace to prevent burnout and overwork.

- Supporting psychological safety by encouraging diverse perspectives.

- Driving better decision-making by fostering a simplicity mindset.

Establishing Norms for our Quarterly Team Health Check

Before we pick up Q1 2025’s team health check I thought it could be useful to attempt to articulate what each tier means, helping to create a shared understanding/ have guides for new starters and as a reference point / helpful reminder.

Below is a guide to interpreting the health check tiers, providing clarity on what each level represents. I encourage collaboration here too – please use the confluence tool capabilities to review and comment or our team sessions to spark conversations that will reduce our implicit assumptions.

| Tier | Description | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Estimations set expectations, manage scope, and foster collaboration and trust across the team and stakeholders. | Estimations align with delivery and are based on meaningful conversations.Historical data is used to improve estimation accuracy.Stakeholders trust the team’s estimates and adapt plans as needed collaboratively. |

| 2 | Estimations are mostly consistent, with occasional deviations that don’t significantly impact delivery. | Estimations align with delivery outcomes most of the time.Discussions are collaborative but may sometimes lack depth or full team participation.General understanding of practices, but some implicit assumptions remain. |

| 3 | Estimations feel arbitrary or disconnected from outcomes, causing friction and inefficiency. | Frequent inconsistency between estimates and actual delivery.Team debates without clarity, or estimations are rushed and lack meaningful discussions.Stakeholders challenge estimates, eroding trust and creating friction. |